We all remember that moment in The Fast and the Furious when Brian O’Conner’s laptop flashes “Warning: Danger to Manifold” before a panel pops off. Cheesy? Absolutely. But we loved it anyway. For many of us, it was our first taste of a world where technology — and a few keystrokes — could make a car faster.

Fast-forward almost 25 years, and cars have changed beyond recognition. Today’s vehicles are rolling computers, packed with complex software, encrypted systems, and safety features. That evolution has brought better performance, security, and convenience, but it’s also made them harder to understand, repair, and modify without deep technical skill.

For aftermarket performance companies, this shift is a major challenge. Tuning a modern car often means breaking through secured software, which not only risks voiding the factory warranty but can also put the shop in hot water with the EPA for violating strict emissions laws. What used to be a straightforward upgrade is now a legal and technical balancing act — where the wrong change could cause serious issues.

This is where DEFCON’s Car Hacking Village (CHV) comes in. For those unfamiliar, DEFCON is the world’s largest hacking convention, held every year in Las Vegas. It draws top minds from around the globe: computer hackers, lockpicking pros, and cybersecurity specialists — all chasing the thrill of solving the toughest technical challenges.

This year, teams of up to 20 cyber gurus went head-to-head hacking two supplied vehicles: the Rivian R1T pickup and the Rivian EDV electric delivery van. Over the course of the weekend, competitors dove into the digital guts of these machines, racing against the clock to unlock doors, trick sensors, and map out internal systems. The entire challenge took place in a safe, controlled environment, testing which team could uncover weaknesses in the software and manipulate the car’s data to their advantage.

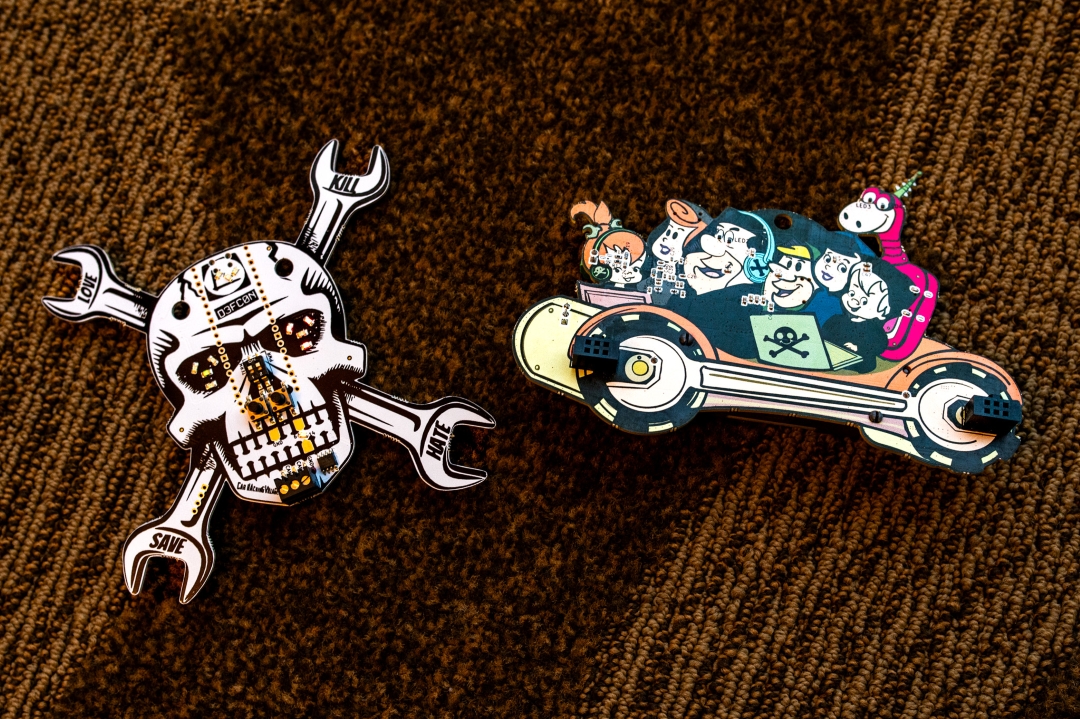

Event organizers had hidden special messages, called “flags,” within each vehicle’s software. Finding a flag meant you had successfully solved that part of the puzzle, and each one was worth a set number of points. The competition followed the classic hacker format known as Capture the Flag (CTF), and by the end of the weekend, the team with the most points walked away with bragging rights, challenge coins, and the satisfaction of digitally breaking into the vehicles.

Isn’t the point to protect vehicles, not teach hackers how to break into them? Yes — but the only way to truly protect something is to understand how it can be attacked. By exposing flaws and demonstrating how they can be exploited, cybersecurity experts can patch weaknesses before criminals get the chance.

While CHV keeps challenges under wraps until the event, this year’s tasks included:

Unlocking the Car – Understanding a locking system and safely opening it without the original key.

Messing with Sensors – Fooling cameras, radar, or parking sensors into misreading their surroundings.

Mapping the Car’s Systems – Tracing messages inside the car’s “nervous system” to see which ones control what.

Firmware/Software Puzzles – Reverse-engineering the code that runs key systems.

Wireless Entry Simulation – Experimenting with key fob signal attacks in a safe testbed.

For example, the vendor floor featured the Flipper Zero for sale — a legal, pocket-sized multi-tool for electronics testing. On its own, it’s harmless. But custom firmware circulating on the dark web can turn it into something far more dangerous, allowing it to bypass Rolling Code Security — the system most modern cars rely on to prevent key fob cloning.

The concerning part? How simple it is. With the altered firmware installed, an attacker only needs to be within range to intercept a single button press from a target’s key fob — say, when the owner locks or unlocks their car. From that one captured signal, they could replicate the digital “key” and potentially gain access without ever touching the original fob.

All of this is done under strict rules: no cheating, no bullying, and no after-hours sneaking.

Outside of hacking competitions, regular car enthusiasts are running into the same wall. In the Fast and Furious era, more speed often meant adding performance parts and turning wrenches. Today, those gains live inside encrypted software that controls the ECU. Manufacturers lock it down with encryption keys, tamper detection, and over-the-air updates that can instantly undo modifications.

These measures:

Help keep cars safe, secure, and within emissions laws.

Also make it harder for hobbyists to personalize or improve performance without advanced technical skills or expensive tools.

Mean even successful tunes can be erased by a software update.

Manufacturers argue this protects drivers and keeps cars compliant. Enthusiasts argue it limits creativity and the freedom to modify their own vehicles. What used to be a hands-on garage hobby is now closer to a computer science project.

With AI now advancing into daily life, it’s becoming even more important for automotive companies to lock down their products — not just to protect customers, but to safeguard their brands. They must defend against enthusiasts trying to crack the software, protect themselves from liability if an incident occurs, and secure their code so hackers can’t steal and copy it.

Whoever controls the code, controls the car.